OK, rant time. Know what sucks? The way our society tells girls and women that are looks are what matter the most. I still get this from certain female relatives who shall remain nameless. First comment when they see me: "Oh, I love your [dress/earrings/shirt/hair]!" It pisses me off because, well... I like the attention. I like being told I look good. Including when it comes from men, because that's how I've been socialized. We learn to desire and seek that attention, and consumerist society gives us all kinds of ways to make ourselves pretty and sexy that generate mega corporate profits.

What really sucks is that the more we focus on our looks, the less we value our intelligence and other gifts and talents.

Case in point: this t-shirt recently made available by J.C. Penney, only to be pulled from its website due to the outrage of parents.

This almost makes me too angry to attempt a proper feminist analysis of how atrocious this is. "Too pretty to do homework" means my looks are way more important than my intellect. Why spend time doing silly homework when I can be trying on makeup or doing my hair? "So my brother has to do it for me." For frig's sake. Leave the thinking to the boys. They're better at it anyway. Go paint your nails, sweetheart. Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr!

I came across a good article the other day on how as a society we really need to work on not dumbing girls down. The best part is how the author, Lisa Bloom, talks about ways of interacting with girls that shift the focus away from looks and towards what girls are thinking about. You know, like asking them what books they're reading. Or what they think about stuff happening in the world.

What if women and girls took all the time we spend on our appearance and invested it in rising up against this bullshit?

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Friday, September 2, 2011

Female Sexual Autonomy Under Siege (Part 4)

Hypersexualization, violence against women and oppression

Hypersexualization naturalizes, encourages and eroticizes violence against women and girls (Kilbourne 2010, Dines 2010). Many studies have shown that hypersexualization is not a separate issue from violence against women and girls, but rather part of a broader picture of violence that includes sexual assault and harassment, physical, psychological and emotional abuse, structural violence (such as poverty, war and racism), cyberviolence (see Sidebar C), and the internalization of misogyny contributing to self-harm, substance abuse, eating disorders, and struggles with depression and anxiety (APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls 2007, Kilbourne 2010, Pipher 1992, Tolman 2002). All of these forms of violence help maintain the current social order that upholds male privilege, and the prospect of women’s sexual liberation threatens this order (Filipovic 2008). When hypersexualization and the less ‘visible’ forms of violence are not enough to keep this power structure in place, men use rape and physical violence (whether knowingly or not) to ensure the continued subjugation of women and girls.

Hypersexualization naturalizes, encourages and eroticizes violence against women and girls (Kilbourne 2010, Dines 2010). Many studies have shown that hypersexualization is not a separate issue from violence against women and girls, but rather part of a broader picture of violence that includes sexual assault and harassment, physical, psychological and emotional abuse, structural violence (such as poverty, war and racism), cyberviolence (see Sidebar C), and the internalization of misogyny contributing to self-harm, substance abuse, eating disorders, and struggles with depression and anxiety (APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls 2007, Kilbourne 2010, Pipher 1992, Tolman 2002). All of these forms of violence help maintain the current social order that upholds male privilege, and the prospect of women’s sexual liberation threatens this order (Filipovic 2008). When hypersexualization and the less ‘visible’ forms of violence are not enough to keep this power structure in place, men use rape and physical violence (whether knowingly or not) to ensure the continued subjugation of women and girls.

There is evidence that this elite media monopoly is indeed being challenged by women and girls who are creating alternative, non-hypersexualizing representations. For example, in Queer Girls and Popular Culture: Reading, Resisting, and Creating Media (2007), Susan Driver discusses the ways in which girls who do not conform to heteronormative expectations are capable of both critiquing and transforming mainstream culture, recognizing that it currently does not reflect the richness and complexity of their realities. With the rise of social media, it seems that new spaces are opening up for youth to redefine culture and our roles within it.

There is evidence that this elite media monopoly is indeed being challenged by women and girls who are creating alternative, non-hypersexualizing representations. For example, in Queer Girls and Popular Culture: Reading, Resisting, and Creating Media (2007), Susan Driver discusses the ways in which girls who do not conform to heteronormative expectations are capable of both critiquing and transforming mainstream culture, recognizing that it currently does not reflect the richness and complexity of their realities. With the rise of social media, it seems that new spaces are opening up for youth to redefine culture and our roles within it.

Dines, G. (2010). Pornland: How porn has hijacked our sexuality. Boston

Debates about consent notwithstanding, violence is a reality with which many women and girls unfortunately continue to live. What this discussion does reveal, however, is that the dominant patriarchal discourse in North America instills men with a fear of women and girls’ sexual power that serves as a basis for control and domination, creating an enabling environment for violence against women and girls. Without indulging in too many statistics, it is worth pointing out that most perpetrators of sexual assault are male and most survivors/victims are female. The rate of violence against women and girls in Canada

Hypersexualization naturalizes, encourages and eroticizes violence against women and girls (Kilbourne 2010, Dines 2010). Many studies have shown that hypersexualization is not a separate issue from violence against women and girls, but rather part of a broader picture of violence that includes sexual assault and harassment, physical, psychological and emotional abuse, structural violence (such as poverty, war and racism), cyberviolence (see Sidebar C), and the internalization of misogyny contributing to self-harm, substance abuse, eating disorders, and struggles with depression and anxiety (APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls 2007, Kilbourne 2010, Pipher 1992, Tolman 2002). All of these forms of violence help maintain the current social order that upholds male privilege, and the prospect of women’s sexual liberation threatens this order (Filipovic 2008). When hypersexualization and the less ‘visible’ forms of violence are not enough to keep this power structure in place, men use rape and physical violence (whether knowingly or not) to ensure the continued subjugation of women and girls.

Hypersexualization naturalizes, encourages and eroticizes violence against women and girls (Kilbourne 2010, Dines 2010). Many studies have shown that hypersexualization is not a separate issue from violence against women and girls, but rather part of a broader picture of violence that includes sexual assault and harassment, physical, psychological and emotional abuse, structural violence (such as poverty, war and racism), cyberviolence (see Sidebar C), and the internalization of misogyny contributing to self-harm, substance abuse, eating disorders, and struggles with depression and anxiety (APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls 2007, Kilbourne 2010, Pipher 1992, Tolman 2002). All of these forms of violence help maintain the current social order that upholds male privilege, and the prospect of women’s sexual liberation threatens this order (Filipovic 2008). When hypersexualization and the less ‘visible’ forms of violence are not enough to keep this power structure in place, men use rape and physical violence (whether knowingly or not) to ensure the continued subjugation of women and girls.When we talk about violence as a means of keeping women and girls in their place, we are really talking about oppression. The word “oppression” originates from fourteenth century Latin and means literally the “action of weighing on someone’s mind or spirits” (Online Etymology Dictionary n.d.). In contemporary times and in the contexts of examining human relations and histories, the word “oppression” is used to refer to the cruel or unfair treatment of one group by another. Feminist thinker bell hooks has developed a theory of oppression that identifies “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” as a system, or rather a system of systems, that enables a small group of people to dominate and exploit the majority (hooks 2004: 17). Her work reveals that there are many forms of oppression such as sexism, racism, classism, homophobia, ableism and colonialism, and they all intersect with and reinforce one another.

According to hooks, all forms of violence that exist in North American society are connected. While violence against women is “an expression of male domination”, she argues that

it is the Western philosophical notion of hierarchical rule and coercive authority that is the root cause of violence against women, of adult violence against children, of all violence between those who dominate and those who are dominated (hooks 1984: 118).

In other words, because our society believes in the right of those in power to abuse the less powerful, we tolerate and encourage sexist, racist and homophobic violence, as well as class exploitation, war and environmental degradation. This is reinforced by the fact that we tend to see relationships of domination and subordination as natural and even based on biological facts (e.g. men are aggressive and women are passive). Until we all challenge this way of thinking in ourselves and others, hooks argues that violence will never disappear and will likely worsen.

Resisting hypersexualization

As the literature shows, hypersexualization is but one form of violence experienced by women and girls in today’s rape culture. When one considers gender-based violence as part of a global context that involves multiple forms of oppression, it is difficult to know just where to begin to resist hypersexualization. Can we end violence against women and girls without ending all forms of oppression?

The answer to this question cannot be found here, but fortunately many others have asked the question and identified numerous ways of constructively challenging hypersexualization. Several of the authors featured in this review have offered up strategies for overcoming rape culture that range from policy reform to revolution, operate at multiple scales, and employ various disciplinary and creative approaches.

In the book Yes Means Yes! Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (Friedman and Valenti 2008), Jill Filipovic highlights the ways in which women are challenging rape culture by promoting a model of “enthusiastic consent” that recognizes female sexual autonomy and women’s right to sexual pleasure and reproductive freedom. She explains that while it is absolutely necessary (and lawful) for men to respect women’s decision not to engage in sexual activity, the usual “no means no” message assumes that women do not want sex and that men cannot control their own sexuality (boys will be boys). Enthusiastic consent is about the right and the ability of women to say yes to the sexual experiences we want, and it fundamentally challenges the gendered paradigm into which most North Americans are socialized. In a broader sense, Filipovic (2008: 25-27) argues that ending rape means challenging oppressive structures and discourses, educating men, asserting women's right to sexual autonomy and reproductive freedom, and promoting a “pleasure-affirming vision of female sexuality.”

The APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls (2007: 4) provides an overview of practical alternatives to (hyper-)sexualization that includes media literacy training in schools, healthy extracurricular activities, “comprehensive sexuality education programs,” creative outlets such as zines and blogs, and girl-specific groups that focus on empowerment. The report also recommends further research on the sexualization of girls, education and training of psychologists and teachers, advocating changes in public policy to address sexualization, and increasing public awareness of the issue.

The APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls (2007: 4) provides an overview of practical alternatives to (hyper-)sexualization that includes media literacy training in schools, healthy extracurricular activities, “comprehensive sexuality education programs,” creative outlets such as zines and blogs, and girl-specific groups that focus on empowerment. The report also recommends further research on the sexualization of girls, education and training of psychologists and teachers, advocating changes in public policy to address sexualization, and increasing public awareness of the issue.

According to Jean Kilbourne (2010), addressing hypersexualization requires setting in motion changes that are “profound and global.” She stresses that we need to think of ourselves primarily as citizens with basic rights rather than consumers. This paradigm shift must occur, she argues, if we are to have “authentic and freely chosen lives”. Kilbourne’s message is echoed by Jackson Katz, who in his documentary Tough Guise (1999) asserts that men are capable of breaking the cycle of violence against women and cultivating healthy masculinities. He emphasizes the importance of “break[ing] the monopoly of the media system,” which is currently controlled by wealthy, white, heterosexual men, in order to allow for a more diverse and healthy range of images and messages to be circulated in our culture (see Sidebar D).

There is evidence that this elite media monopoly is indeed being challenged by women and girls who are creating alternative, non-hypersexualizing representations. For example, in Queer Girls and Popular Culture: Reading, Resisting, and Creating Media (2007), Susan Driver discusses the ways in which girls who do not conform to heteronormative expectations are capable of both critiquing and transforming mainstream culture, recognizing that it currently does not reflect the richness and complexity of their realities. With the rise of social media, it seems that new spaces are opening up for youth to redefine culture and our roles within it.

There is evidence that this elite media monopoly is indeed being challenged by women and girls who are creating alternative, non-hypersexualizing representations. For example, in Queer Girls and Popular Culture: Reading, Resisting, and Creating Media (2007), Susan Driver discusses the ways in which girls who do not conform to heteronormative expectations are capable of both critiquing and transforming mainstream culture, recognizing that it currently does not reflect the richness and complexity of their realities. With the rise of social media, it seems that new spaces are opening up for youth to redefine culture and our roles within it. Conclusion

What does redefining culture look like? This is an area where more research is needed, particularly with regard to alternatives to hypersexualization. While we have a variety of tools at our disposal for critiquing and deconstructing gender roles, overcoming hypersexualization requires a cultural process of constructing healthy masculinities and femininities, and a serious look at how we can redefine “sexy” so that it connotes both pleasure and safety for women and adolescent girls. The voices and stories of youth are crucial in this process of renegotiation, and supportive adults have an important role to play in opening up spaces in which these conversations can happen.

References

APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls: Executive summary. Washington , DC

Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women. (2002). Violence against Women and Girls (CRIAW Fact Sheet). Retrieved 03/30, 2011, from http://criaw-icref.ca/ViolenceagainstWomenandGirls

Driver, S. (2007). Queer Girls and Popular Culture: Reading New York

Filipovic, J. (2008). Offensive feminism: The conservative gender norms that perpetuate rape culture, and how feminists can fight back. In J. Friedman, & J. Valenti (Eds.), Yes Means Yes: Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape (pp. 13-27). Berkeley , California

Friedman, J. and J. Valenti (Eds.). (2008). Yes Means Yes: Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape. Berkeley , California

hooks, b. (1984). Feminist Theory: From margin to center. Cambridge , MA

hooks, b. (2004). The Will to Change: Men, masculinity, and love. New York

Katz, J. (Director), Tough Guise: Violence, media, and the crisis in masculinity. (1999). [Video/DVD]

Kilbourne, J. (Director), Killing Us Softly 4: Advertising's image of women. (2010). [Video/DVD]

Online Etymology Dictionary. (n.d.). Oppression. Retrieved 03/24, 2011, from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/oppression

Pipher, M. (1994 and 1992). Reviving Ophelia: Saving the selves of adolescent girls. USA

Tolman, D. L. (2002). Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. USA : First Harvard University

Yes Means Yes: Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape. Berkeley , California

Monday, August 29, 2011

Female Sexual Autonomy Under Siege (Part 3)

Masculinity and rape culture

Not all men are equally privileged through this patriarchal discourse. Heterosexual men, particularly those who enjoy other forms of social and economic privilege, are at the top of a hierarchy of masculinity that devalues and dehumanizes all others (Newton 2007, Taylor 2011). These men are the ‘subjects’ of the discourse, and subjectivity is dependent on to what extent one measures up to normative masculinity. Because of this, gay and bisexual men (or men who are perceived as such) are feminized and dehumanized, and therefore are also vulnerable to violence. Women and girls are – not surprisingly – very low on this hierarchy, as are lesbian and bisexual women, transfolk, women of color, working-class women, disabled women, and Aboriginal women. We all suffer from not being heterosexual males, which is considered the norm and the ultimate expression of humanity (Connell 2005, Taylor 2011).

Female sexual autonomy and consent

So how do women consent to sex when our sexual subjectivity is so limited in our culture? We know from sexual assault awareness and prevention campaigns that “no means no”, but what does “yes” mean? It is easy to assume that “yes” means “yes”, but consent does not always entail a positive sexual experience for both partners. On university campuses in particular, the prevalence of (legally) consensual but regrettable sexual experiences has led to discussions around an issue that is hardly new, but only recently has been named as “unwanted consensual sex” (Cole 2010). According to Yale student and journalist Jessica Cole (2010):

Newton

It is important to consider that these messages do not only affect girls. The socialization of boys is just as critical to the reproduction of rape culture as the socialization of girls. From a very early age, boys learn to associate strength with dominance and gentleness with weakness and femininity (or homosexuality) (Kilbourne 2010, Newton 2007). Later on in life as adolescents, boys learn to view themselves as entitled to women’s bodies and to avoid or mask their emotional vulnerability (Kimmel 2000). These learned behaviors and attitudes are part of a discourse (the socially embedded ‘rules’ in language that influence what people understand as truth or common sense – see Foucault 1972) that contributes to rape culture. The discourse tells us that men are sexually active and women are sexually passive, that “boys will be boys”, and that as women and girls we need to protect ourselves from men’s unchecked sexuality (Kilbourne 2010). This assumption that men are more sexual than women, and that men cannot control their own sexuality, unfairly places the onus on women and girls to put safety before pleasure and to prevent rape (Tolman 2002, Friedman 2008).

Not all men are equally privileged through this patriarchal discourse. Heterosexual men, particularly those who enjoy other forms of social and economic privilege, are at the top of a hierarchy of masculinity that devalues and dehumanizes all others (Newton 2007, Taylor 2011). These men are the ‘subjects’ of the discourse, and subjectivity is dependent on to what extent one measures up to normative masculinity. Because of this, gay and bisexual men (or men who are perceived as such) are feminized and dehumanized, and therefore are also vulnerable to violence. Women and girls are – not surprisingly – very low on this hierarchy, as are lesbian and bisexual women, transfolk, women of color, working-class women, disabled women, and Aboriginal women. We all suffer from not being heterosexual males, which is considered the norm and the ultimate expression of humanity (Connell 2005, Taylor 2011).

Female sexual autonomy and consent

How does this affect women’s and girls’ lives and the way we experience our sexuality? According to Tolman (2002), what’s missing from the dominant, male-centric discourse of sexuality is the idea of female sexual autonomy or “sexual subjectivity”, which is the capacity to be agents of our own sexuality. Hypersexualization undermines female sexual autonomy because it sends the message that women and girls are sexual objects without a right to pleasure or safety. Heterosexuality as it is experienced through our culture is centered on male pleasure, and because female sexual desire threatens to destabilize this patriarchal value system it is often depicted as dirty, dangerous or sinful (Filipovic 2008, Tolman 2002).

Indeed, women and girls are subject to what many refer to as the “Madonna/whore dichotomy” (Tolman 1994): our culture tells us to be chaste, gentle and faithful to heterosexual partners, yet we are also expected to be skinny, waxed, big-breasted (through surgery if need be), and heterosexually promiscuous. The problem is that neither archetype allows any room for female sexual autonomy or for acknowledgement of women’s wholeness as human beings. If we are well-behaved women, we are praised and celebrated but still expected to fulfill our role as homemakers and reproducers. If we perform the latter role, we are labeled as whores and sometimes even accused of ‘asking for rape’ (see Sidebar B).

So how do women consent to sex when our sexual subjectivity is so limited in our culture? We know from sexual assault awareness and prevention campaigns that “no means no”, but what does “yes” mean? It is easy to assume that “yes” means “yes”, but consent does not always entail a positive sexual experience for both partners. On university campuses in particular, the prevalence of (legally) consensual but regrettable sexual experiences has led to discussions around an issue that is hardly new, but only recently has been named as “unwanted consensual sex” (Cole 2010). According to Yale student and journalist Jessica Cole (2010):

“Unwanted consensual sex” is... a decidedly gray area. Unlike rape or sexual assault, it is not a disciplinary or criminal offense. At its core, the phrase refers to sex that may, for one reason or another, be regretted.

Understanding the issue of unwanted consensual sex requires looking “beyond yes and no” and viewing “consent as sexual process” (Kramer Bussel 2008). This means examining the context of sex, including how each person is feeling, what the power dynamic is, and the ways in which men learn to “manufacture consent” through various forms of manipulation (Atherton-Zeman 2006). It also requires an examination of the broader culture, including hypersexualization and the many ways in which women and girls are pressured to engage in sexual activities that they do not enjoy (Pipher 1992, Tolman 2002).

There is a danger, however, in the idea of “gray rape” or that it is hard to define rape when so many factors (such as culture, relational dynamics and alcohol consumption) are involved (Jervis 2008). The patriarchal backlash against anti-rape activism has taken the form of this argument, and feminists continue to struggle for the creation and maintenance of laws that hold rapists criminally responsible for their actions (Hakvåg 2010). Hedda Hakvåg (2010) argues that while backlash thinkers are correct in noting the difficulty in distinguishing between rape and sexual coercion, the “gray rape” discourse supports an anti-woman agenda because it suggests that rape is an arbitrary category and is thus impossible to criminalize. She calls for a feminist examination of “sexual coercion in normative heterosexuality”, meaning that we need to look critically at male power in heterosexual relationships, the ways in which violence against women is naturalized in our culture, and the internalization of misogyny that makes sexual consent difficult, if not (and this is a major debate among feminists) impossible within the current social order.

References

CBC News. (2011). Judge's sex-assault remarks under review. Retrieved 03/17, 2011, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/story/2011/02/25/mb-dewar-comments-review-judicial-council-winnipeg.html

Cole, J. (2010, November 17). "Yes" means "no"?: A workshop on unwanted conensual sex. Broad Recognition: A Feminist Magazine at Yale, Retrieved 03/30, 2011, from http://www.broadrecognition.com/sex-health/yes-means-no-a-workshop-on-unwanted-consensual-sex/

Filipovic, J. (2008). Offensive feminism: The conservative gender norms that perpetuate rape culture, and how feminists can fight back. In J. Friedman, & J. Valenti (Eds.), Yes Means Yes: Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape (pp. 13-27). Berkeley , California

Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge (A. M. Sheridan Smith Trans.). New York

Friedman, J. (2008). In defense of going wild or: How I stopped worrying and learned to love pleasure (and how you can, too). In J. Friedman, & J. Valenti (Eds.), Yes Means Yes: Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape. Berkeley , California

Hakvåg, H. (2010). Does yes mean yes? exploring sexual coercion in normative heterosexuality. Canadian Woman Studies, 28(1)

Jervis, L. (2008). An old enemy in a new outfit: How date rape became gray rape and why it matters. In J. Friedman, & J. Valenti (Eds.), Yes Means Yes! Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape. Berkeley

Kilbourne, J. (Director), Killing Us Softly 4: Advertising's image of women. (2010). [Video/DVD]

Kimmel, M. (2000). The Gendered Society. New York : Oxford University

Kramer Bussel, R. (2008). Beyond Yes or No: Consent as sexual process. In J. Friedman, & J. Valenti (Eds.), Yes means yes: Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape. Berkeley , California

Pipher, M. (1994 and 1992). Reviving Ophelia: Saving the selves of adolescent girls. USA

Taylor, E. (2011). Erasing the Feminine: The construction of masculinity in initiation rites. (Unpublished.) St. Francis Xavier University

Tolman, D. L. (1994). Doing desire: Adolescent girls' struggles for/with sexuality. Gender and Society, 8(3), 324-342.

Tolman, D. L. (2002). Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. USA : First Harvard University

Friday, August 26, 2011

Female Sexual Autonomy Under Siege (Part 2)

Hypersexualization in the 21st century

(The hypersexualization of women and girls in the media often has a racist dimension. In Killing Us Softly (2010), Jean Kilbourne explains how Black women are frequently depicted in ads as animals, which serves to dehumanize them. We also see images that portray Aboriginal women as sexual objects and cultural ‘others’.)

References

Dines, G. (2010). Pornland: How porn has hijacked our sexuality.Boston

American feminist Jean Kilbourne has created a series of films called Killing Us Softly, which documents and examines the images of women that appear in advertising. There have been four installments of the film, the first released in 1979 and the latest released in 2010, and in each version Kilbourne delivers the same speech about the objectification and exploitation of women’s bodies in advertising, but accompanied by a set of current images. At the beginning of Killing Us Softly 4 (2010) Kilbourne says:

Sometimes people say to me, ‘You’ve been talking about this for 40 years. Have things gotten any better?’ And actually I have to say, really they’ve gotten worse.

Indeed, things have gotten worse. Since 1979 we have witnessed the rise of neoliberal globalization marked by a series of transformations in the direction of smaller governments, social program cutbacks, increasing poverty and inequality, and the religious fervor of ‘free-market’ ideology. Emerging from this period of transition was a backlash against feminism, the mainstreaming of pornography (Dines 2010) and the emergence of post-feminism. A product of this post-feminist and consumeristic environment was Girl Power, which began as a culture of young female empowerment but quickly became a vehicle for the depoliticization of gender issues, the commodification and co-optation of feminism, and the hypersexualization of women and girls (Gonick 2006).

Since the 1990s there has arguably been an increase in the pervasiveness and intensity of cultural representations that have hypersexualizing effects on women and girls. The term ‘hypersexualization’ refers to the process through which images and messages that sexually objectify women and girls are circulated, experienced and internalized by members of society. In today’s hypersexualized culture, women and girls are pressured to conform to these images and invest an incredible amount of time, energy and money into our appearances. These images objectify and dehumanize women and girls, represent us as consumable bodies rather than as whole human beings, and normalize and eroticize male violence against women. They are often racist, heterosexist, and based on an unattainable standard of beauty. Corporations use these images not only to sell products, but as Kilbourne (2010) explains, to sell values, attitudes and ideas of what is ‘normal’.

(The hypersexualization of women and girls in the media often has a racist dimension. In Killing Us Softly (2010), Jean Kilbourne explains how Black women are frequently depicted in ads as animals, which serves to dehumanize them. We also see images that portray Aboriginal women as sexual objects and cultural ‘others’.)

Yeah, but we’re too smart for that, right? Hypersexualization as a cultural process with real effects on women and girls

It’s tempting to think that these images don’t affect us, or that their influence is merely superficial. Studies have shown, however, that hypersexualization has a very real impact on women and girls – and it’s not good. The American Psychological Association Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls released a report (2007) that explains the psychological impact of hypersexualization on women and girls including cognitive difficulties, negative emotions, eating disorders, low self-esteem, depression, poor sexual health, negative sense of one's sexuality, and the internalization of misogynistic (woman-hating) attitudes. The report also identifies a number of societal effects of hypersexualization including sexism, the limiting of opportunities for girls and young women, increasing sexual harassment, sexual violence, and the prevalence of child pornography.

How does this all happen? According to Jill Filipovic (2008), we live in a “rape culture” that normalizes violence against women through a patriarchal ideology that teaches men they are entitled to women’s bodies, and seeks to deny women the right to bodily autonomy and economic and social equality. This ideology, which is circulated by social conservatives including the religious right, helps maintain the patriarchal status quo which is threatened by anti-rape laws and the idea that men are responsible for preventing rape. Also threatening is the possibility of women claiming the freedom to make decisions about their bodies, families, work, finances and education – in other words, women enjoying the same human rights as men. Therefore, patriarchal society uses rape (or fear of rape) as a means of controlling women’s lives and maintaining male power and privilege.

Hypersexualization is part of this rape culture, and while cultural images and messages do not directly cause violence against women and girls, they certainly encourage and enable it through the dehumanization of women and objectification of our bodies (Kilbourne 2010). By making women feel perpetually inadequate about our appearance and sexual attractiveness, corporations profit from women and girls’ insecurity and contribute to a vicious cycle of depression, anxiety, eating disorders and self-harm. Moreover, the internalization of misogyny carries through into our careers and all other aspects of lives, making all women (in some way) survivors of hypersexualization. Kilbourne (2010) rightly names this issue as a “public health problem”.

Mary Pipher explores the effect of this problem on adolescent girls in her book Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls (1994). She argues that children are socialized into a “girl-poisoning culture” that makes it nearly impossible for girls to develop good self-esteem, positive body image and healthy sexuality. The book states that girls “are coming of age in a more dangerous, sexualized and media-saturated culture” and need to be equipped with better tools for navigating this culture (Pipher 1994: 12). While Reviving Ophelia made a significant contribution to understanding the dangers of growing up female in an increasingly misogynistic world, it has been criticized for portraying girls as passive victims and failing to situate their experiences within broader social, economic and political contexts (Gonick 2006).

A different approach to understanding girls’ experiences is found in Deborah L. Tolman’s Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage Girls Talk About Sexuality (2002). Tolman’s research involved asking adolescent girls to speak about their desire, a question that girls are not usually asked since we live in a society that fears, seeks to control and therefore renders taboo female sexuality. She framed her study with the understanding that:

Girls live and grow up in bodies that are capable of strong sexual feelings, bodies that are connected to minds and hearts that hold meanings through which they make sense of and perceive their bodies. I consider the possibility that teenage girls’ sexual desire is important and life sustaining; that girls’ desire provides crucial information about the relational world in which they live; that the societal obstacles to girls’ and women’s ability to feel and act on their own desire should come under scrutiny rather than simply be feared; that girls and women are entitled to have sexual subjectivity, rather than simply to be sexual objects. (Tolman 2002: 19)

The stories of the adolescent girls Tolman interviewed revealed that girls do indeed experience desire, but in order to express this desire they must navigate a complicated world in which their pleasure and safety do not always coincide. While Tolman identifies many of the same risk factors (such as violence and sexual coercion) that Pipher does, she also emphasizes the positive experiences girls have with desire and pleasure, all within an analysis that considers the socially constructed nature of gender relations. Perhaps most significantly, Tolman’s book involves adolescent girls telling their own stories in their own voices, generating knowledge that gives readers a deeper understanding of their multifaceted experiences.

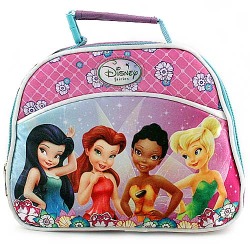

While adolescence is a particularly challenging time for girls and their struggle with hypersexualization, the messages and images that shape our sexuality and sense of self are introduced at a very early age. (Case in point: the Tinker Bell lunch bag.) We observe hypersexualization in way the girls are taught to enjoy dolls and dressing up while boys are sent outside to play. While boys learn that it’s important to be strong and active, girls learn to be passive and that their looks are what matters the most (Kilbourne 2010). Indeed, young girls are groomed for a future of sexual servitude through a “princess culture” (Orenstein 2010) that is as consumeristic as it is misogynistic, and is a precondition for the rape culture in which adolescent girls and women struggle to survive. The basis of princess culture is a simple narrative with which most of us are quite familiar: strive to be nice and pretty, and someday you will find a strong handsome man who will sweep you off your feet and you will live happily ever after.

For girls growing up today, however, the narrative is not so simple. In the past two decades, the messages that influence gender socialization have become increasingly sexualized and pornographized. The film Sexy Inc.: Our Children Under Influence (Bissonnette 2007) shows how corporations are invading the space of childhood by encouraging young girls and boys to consume images that sexually objectify women and promote dominant male behavior. Girls learn to value their appearance over other qualities, and they are compelled to mimic the latest adult fashion trends that include tight, revealing clothing, heavy makeup and sexy lingerie. This phenomenon, which would have been met with public outrage only a few years ago, is normalized through advertisements that both infantilize adult women and portray children in adult and even pornographic situations. As one speaker in the film summarizes this disturbing reality, “we are stealing childhood away from children” (Bissonnette 2007).

(An image from Bratz, a company that markets dolls, fashions, toys and games to young girls.)

References

APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls: Executive summary. Washington , DC

Bissonnette, S. (Director), Sexy Inc.: Our children under influence. (2007). [Video/DVD]

Dines, G. (2010). Pornland: How porn has hijacked our sexuality.

Filipovic, J. (2008). Offensive feminism: The conservative gender norms that perpetuate rape culture, and how feminists can fight back. In J. Friedman, & J. Valenti (Eds.), Yes Means Yes: Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape (pp. 13-27). Berkeley , California

Gonick, M. (2006). Between "Girl Power" and "Reviving Ophelia": Constituting the neoliberal girl subject. NWSA Journal, 18(2)

Kilbourne, J. (Director), Killing Us Softly 4: Advertising's image of women. (2010). [Video/DVD]

Orenstein, P. (2010). Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches from the front lines of the new girlie-girl culture. New York

Pipher, M. (1994 and 1992). Reviving Ophelia: Saving the selves of adolescent girls. USA

Tolman, D. L. (2002). Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. USA : First Harvard University

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Female Sexual Autonomy Under Siege (Part 1)

Hi folks! This is the first of a series of posts on the issue of hypersexualization that I plan to share over the next few weeks. They are part of a literature review I conducted this past spring through my work with the Resisting Violence project at the Antigonish Women's Resource Centre & Sexual Assault Services Association. Read on...

Introduction

Not long ago I spent a weekend in a small university town with my cousin, who lives in a communal house with friends who are artists and activists. The house is characterized by wood floors and walls, colorful carpets, hip posters, musical instruments and organic food. You can imagine my surprise, then, when I was in the kitchen having a glass of water and noticed a hot pink lunch bag sitting on a nearby counter. Upon further inspection, I discovered that it was a Disney “Tinker Bell and Fairies” lunch bag (see image below), and its front displayed an image of four attractive women – or were they girls? I soon came to the alarming realization that these characters were indeed supposed to be girls, but they had unusually womanish features and were arranged in sexually inviting yet childishly innocent poses. Irritated, I thought: “Why are we exposing girls to such awful images, and what is this lunch bag doing in a hippy house?”

The second question I will leave for a later conversation with my cousin and her housemates. The first question, though, demands some immediate attention. As a society, are we fully aware of the impact of such images on our daughters and sons? As women, do we know how these images have affected and continue to affect our body image, self-esteem and sexuality?

I decided to investigate the story of this lunch bag a little further, and I discovered that there is a whole range of paraphernalia containing images of Tinker Bell and her fairy friends that can be purchased online, including fairy costumes, toys, home décor products, collectibles and accessories. I then did a Google image search of Tinker Bell and fairies, and it generated an assortment of images that confirmed my suspicion that this stuff is far from innocent. Two words quickly came to mind: child pornography.

Introduction

Not long ago I spent a weekend in a small university town with my cousin, who lives in a communal house with friends who are artists and activists. The house is characterized by wood floors and walls, colorful carpets, hip posters, musical instruments and organic food. You can imagine my surprise, then, when I was in the kitchen having a glass of water and noticed a hot pink lunch bag sitting on a nearby counter. Upon further inspection, I discovered that it was a Disney “Tinker Bell and Fairies” lunch bag (see image below), and its front displayed an image of four attractive women – or were they girls? I soon came to the alarming realization that these characters were indeed supposed to be girls, but they had unusually womanish features and were arranged in sexually inviting yet childishly innocent poses. Irritated, I thought: “Why are we exposing girls to such awful images, and what is this lunch bag doing in a hippy house?”

(The culprit: A typical accessory marketed by Disney to young girls.) | <><>

I decided to investigate the story of this lunch bag a little further, and I discovered that there is a whole range of paraphernalia containing images of Tinker Bell and her fairy friends that can be purchased online, including fairy costumes, toys, home décor products, collectibles and accessories. I then did a Google image search of Tinker Bell and fairies, and it generated an assortment of images that confirmed my suspicion that this stuff is far from innocent. Two words quickly came to mind: child pornography.

I will not indulge in a full critical analysis of this image – the presence of the male gaze, the (only somewhat) subtle racism, and the downright pornographization of children – but the point of this story is merely to highlight that this stuff is everywhere. Even in the places where we least expect to find it.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Taking Root promo vid!

Registration for "Taking Root", a creative peacebuilding workshop for youth, has been extended to Wednesday, August 17. Online registration is at http://www.planetreg.com/E715841897 . Check out our rad promo vid!

Thursday, August 11, 2011

"Taking Root" creative peacebuilding workshop

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

“Taking Root” workshop to engage youth in social justice leadership

Antigonish, NS, August 11, 2011— This summer youth will gather in Antigonish to explore creative ways of engaging with social justice issues. Presented through the Resisting Violence project of the Antigonish Women’s Resource Centre, “Taking Root” will happen on August 19-20 at People’s Place Library.

Through a series of hands-on learning activities, participants in this creative peacebuilding workshop will develop skills in facilitation, feminist analysis of oppression, and nonviolent action.

A call for participation has been issued to youth age 16-22 in Antigonish and Guysborough counties and the Strait area. The workshop will be facilitated by a group of young persons including AWRC staff and members of the Antigonish community.

On Friday, August 19 there will be a coffeehouse to open the workshop and introduce its themes to participants and the broader community. It will be held at the StFX Art Gallery

Saturday, August 20 will involve a full day of skill-building and learning. Participants will discover new ways of expressing their voice through activities such as radical cheerleading, zine-making and active citizenship practices.

“I believe that creative expression is one of the best responses to violence”, says workshop co-organizer and Resisting Violence project coordinator Betsy MacDonald. “By rooting ourselves in an understanding of the interconnectedness of all life, we can cultivate peaceful ways of being in the world.”

The full schedule and online registration for “Taking Root” can be found at http://www.planetreg.com/E715841897 . Registration is open until Monday, August 15.

The Resisting Violence project is funded by Status of Women Canada.

###

Contact: Jillian Hennick

Antigonish Women’s Resource Centre & Sexual Assault Services Association

(902) 863-6221

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

How to communicate like a man... or not

Today a piece of mail arrived at the Women’s Centre. It contained information about an upcoming seminar, happening this August in various Canadian locations, on “Communication Skills for Women”.

Here’s what it said…

Communication Skills for Women

The top 10 communication hurdles – can you relate?

Our researchers asked women across the country to describe their toughest communication situations. We analyzed more than 800 circumstances and came up with these top 10:

1) Confronting or criticizing others

2) Not being taken seriously

3) Feeling self-conscious

4) Dealing with other people’s anger

5) Speaking in front of a group

6) Controlling one’s emotions

7) Receiving criticism

8) Getting cooperation

This one-day training will help you build the skills to overcome them.

The flyer went on to describe ways that women will benefit from the seminar, such as…

You’ll stay cool even when you’ve reached your boiling point. You can’t back down and expect to move ahead. Yet maybe you, like many women, avoid conflict… or flood emotionally and have a hard time thinking and acting clearly.

Needless to say, upon reading this I was “flooded” with emotion and felt compelled to respond. Below is my answer to “Communication Skills for Women”…

Communication Skills for Men

How to achieve compassion, empathy and caring in the workplace

The top 10 communication hurdles – can you relate?

Our researchers asked men across the country to describe their toughest communication situations. We analyzed more than 800 circumstances and came up with these top 10:

Betsy

Here’s what it said…

Communication Skills for Women

How to achieve confidence, credibility, and composure in the workplace

The top 10 communication hurdles – can you relate?

Our researchers asked women across the country to describe their toughest communication situations. We analyzed more than 800 circumstances and came up with these top 10:

1) Confronting or criticizing others

2) Not being taken seriously

3) Feeling self-conscious

4) Dealing with other people’s anger

5) Speaking in front of a group

6) Controlling one’s emotions

7) Receiving criticism

8) Getting cooperation

9) Setting limits

10) Taking the floor

This one-day training will help you build the skills to overcome them.

The flyer went on to describe ways that women will benefit from the seminar, such as…

You’ll stay cool even when you’ve reached your boiling point. You can’t back down and expect to move ahead. Yet maybe you, like many women, avoid conflict… or flood emotionally and have a hard time thinking and acting clearly.

Needless to say, upon reading this I was “flooded” with emotion and felt compelled to respond. Below is my answer to “Communication Skills for Women”…

Communication Skills for Men

How to achieve compassion, empathy and caring in the workplace

The top 10 communication hurdles – can you relate?

Our researchers asked men across the country to describe their toughest communication situations. We analyzed more than 800 circumstances and came up with these top 10:

1) Listening to others

2) Taking yourself too seriously

3) Feeling over-confident

4) Dealing with your ego

5) Knowing when to stop talking

6) Acknowledging and working with your emotions

7) Receiving advice without getting defensive

8) Cooperating

9) Letting go of the need to control

10) Not dominating the floor

This one-day training will help you build the skills to overcome them.

Maybe a parallel seminar for men is in order?

Betsy

Monday, May 9, 2011

Women's Action Coalition - Nova Scotia (WAC-NS) General Assembly

Do you want women’s concerns on the public agenda?

Do you want your voices amplified and echoed by women across the province?

Do you want every woman and girl in Nova Scotia to know that her well-being is critical to the well-being of our province and country?

If you answered yes to these questions, then you should attend

The first Annual General Assembly of the Women’s Action Coalition – Nova Scotia (WAC-NS).

The WAC-NS is a broad- based non-partisan alliance of women’s groups and committees, social justice organizations and individuals concerned with women’s equality. Active in the 1980s and 1990s, WAC-NS is being re-constituted in response to decisions that are being made at the national, provincial and municipal levels about issues that have disproportionate impacts on women. We want our governments to know that we are concerned that:

• many women and families in our province are living in poverty

• childcare is a luxury rather than a right

• affordable housing is limited and inadequate

• violence against women is widespread

• the cost of education is prohibitive for many women

• too many women are working in low-paying, insecure jobs

• women’s services are under-funded

JOIN US!

What: WAC-NS First Annual General Assembly

When: Saturday, May 14, 2011 9.00a.m. to 4.30.p.m.

Where: McNally Auditorium, McNally Main Building, Saint Mary’s University, Robie Street, Halifax

Join the Women’s Action Coalition and register for the Assembly! For more information contact:

Stella Lord: lords@eastlink.ca

Do you want your voices amplified and echoed by women across the province?

Do you want every woman and girl in Nova Scotia to know that her well-being is critical to the well-being of our province and country?

If you answered yes to these questions, then you should attend

The first Annual General Assembly of the Women’s Action Coalition – Nova Scotia (WAC-NS).

The WAC-NS is a broad- based non-partisan alliance of women’s groups and committees, social justice organizations and individuals concerned with women’s equality. Active in the 1980s and 1990s, WAC-NS is being re-constituted in response to decisions that are being made at the national, provincial and municipal levels about issues that have disproportionate impacts on women. We want our governments to know that we are concerned that:

• many women and families in our province are living in poverty

• childcare is a luxury rather than a right

• affordable housing is limited and inadequate

• violence against women is widespread

• the cost of education is prohibitive for many women

• too many women are working in low-paying, insecure jobs

• women’s services are under-funded

JOIN US!

What: WAC-NS First Annual General Assembly

When: Saturday, May 14, 2011 9.00a.m. to 4.30.p.m.

Where: McNally Auditorium, McNally Main Building, Saint Mary’s University, Robie Street, Halifax

Join the Women’s Action Coalition and register for the Assembly! For more information contact:

Stella Lord: lords@eastlink.ca

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Fund a Feminist - RebELLEs Gathering 2011

(From the FemRev collective:)

Attention Feminists and allies!

As the Organizing Committee, FemRev is busy getting ready for the RebELLEs: Notre Révolution Féministe, Our Revolution is Now, we are still short a large amount of funds to be able to pull off the gathering as best we can! We are calling on feminists and allies across the country to help support us in making this possible!

FemRev is launching the Fund a Feminist Campaign in order to help bring to fruition a project aimed at giving a voice to young women of Canada and encouraging them to participate actively in community life. FemRev is working hard to organize the 2nd ReELLEs Pan-Canadian Young Feminist Gathering Notre Révolution Féministe, Our Revolution is Now, to take place in Winnipeg from May 20-23, 2011. The first was held in Montreal in 2008 and was attended by more than 500 dedicated young women from every Canadian province and territory, as well as international delegates from the World March of Women. The 2011 Gathering will work to empower young women and girls, to mobilize, energize, and provide opportunities for these women and girls to develop leadership skills, collectively work to improve the lives of young women, and to work within diversity in order to make meaningful contributions to the communities we are a part of. It is an opportunity to collectivize our struggles and create concrete plans for change.

We must raise funds to cover all aspects of the gathering with the most crucial costs being transportation subsidies (especially for women from rural and Northern communities), French/English/American Sign Language translation and interpretation services, healthy meals, accommodation subsidies, rental space, and printing and promotion costs.

FemRev is launching the Fund a Feminist Campaign and we need your help!

We would like to ask you to show your support by making a monetary donation or by covering the cost of specific expenses such as transportation, lodging, food, etc. Your contribution would demonstrate your commitment to improving women’s lives in Canada and across the globe, and would support young women’s efforts to improve women’s political, economic, and social conditions.

What could your contribution help support?!

$1 - $5 - The cost of a meal for one young feminist

$10 - $20 - One night’s accommodation for one young feminist

$30 - $40 - The cost of printing 50 posters for distribution nationally

$50 - $60 - The costs related to renting one of the workshop venues

$ 75 - An honorarium for a workshop facilitator

$ 100 - The cost of an honorarium for a performer at the Feminist Cabaret

$ 200 - Covers 1 hour of translation services so that the gathering is accessible in French, English and ASL.

$ 250+ - Help a young women with her travel costs to the gathering

How to Donate

Paypal – donation button online at www.rebelles.org

Cheque – Made payable to FemRev Collective

Mail: FemRev

2F, 91 Albert Street

Winnipeg, Mb

R3B 1G5

Canada

For more information about RebELLEs and the gathering, visit us www.rebelles.org.

We hope you will consider supporting this important event!

In solidarity,

FemRev, the RebELLEs Organizing Committee 2011

rebelles@femrev.org or (204)942-7390

Attention Feminists and allies!

As the Organizing Committee, FemRev is busy getting ready for the RebELLEs: Notre Révolution Féministe, Our Revolution is Now, we are still short a large amount of funds to be able to pull off the gathering as best we can! We are calling on feminists and allies across the country to help support us in making this possible!

FemRev is launching the Fund a Feminist Campaign in order to help bring to fruition a project aimed at giving a voice to young women of Canada and encouraging them to participate actively in community life. FemRev is working hard to organize the 2nd ReELLEs Pan-Canadian Young Feminist Gathering Notre Révolution Féministe, Our Revolution is Now, to take place in Winnipeg from May 20-23, 2011. The first was held in Montreal in 2008 and was attended by more than 500 dedicated young women from every Canadian province and territory, as well as international delegates from the World March of Women. The 2011 Gathering will work to empower young women and girls, to mobilize, energize, and provide opportunities for these women and girls to develop leadership skills, collectively work to improve the lives of young women, and to work within diversity in order to make meaningful contributions to the communities we are a part of. It is an opportunity to collectivize our struggles and create concrete plans for change.

We must raise funds to cover all aspects of the gathering with the most crucial costs being transportation subsidies (especially for women from rural and Northern communities), French/English/American Sign Language translation and interpretation services, healthy meals, accommodation subsidies, rental space, and printing and promotion costs.

FemRev is launching the Fund a Feminist Campaign and we need your help!

We would like to ask you to show your support by making a monetary donation or by covering the cost of specific expenses such as transportation, lodging, food, etc. Your contribution would demonstrate your commitment to improving women’s lives in Canada and across the globe, and would support young women’s efforts to improve women’s political, economic, and social conditions.

What could your contribution help support?!

$1 - $5 - The cost of a meal for one young feminist

$10 - $20 - One night’s accommodation for one young feminist

$30 - $40 - The cost of printing 50 posters for distribution nationally

$50 - $60 - The costs related to renting one of the workshop venues

$ 75 - An honorarium for a workshop facilitator

$ 100 - The cost of an honorarium for a performer at the Feminist Cabaret

$ 200 - Covers 1 hour of translation services so that the gathering is accessible in French, English and ASL.

$ 250+ - Help a young women with her travel costs to the gathering

How to Donate

Paypal – donation button online at www.rebelles.org

Cheque – Made payable to FemRev Collective

Mail: FemRev

2F, 91 Albert Street

Winnipeg, Mb

R3B 1G5

Canada

For more information about RebELLEs and the gathering, visit us www.rebelles.org.

We hope you will consider supporting this important event!

In solidarity,

FemRev, the RebELLEs Organizing Committee 2011

rebelles@femrev.org or (204)942-7390

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

May is Sexual Assault Awareness Month. It's time... to get involved!

It's time to get involved in sexual assault awareness and prevention! May is Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM) and we will be proclaiming this tomorrow in Antigonish at the AWRC & SASA at 10am - all are welcome! Stay tuned for more information throughout the month. Here's a message from Avalon Sexual Assault Centre...

“It’s time…to talk to your family.” Sexual violence is a difficult subject to talk about in families. Many victims/survivors are afraid to tell their families about sexual abuse/assault out of fear of how they may respond. Families may be unsure how to support family members who have been sexually victimized. Avalon Centre provides information, emotional support, and legal support/advocacy for non offending parents/family members children who have experienced sexual violence. For more information contact 422-4240. Check out this family scenario activity: http://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/file/saam/saam_2011-ScenarioFamily.pdf.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Resisting Violence page up and running!

Good morning! And good news... the web page for the Resisting Violence project is now up and running! To give a bit of context, "Resisting Violence: Rural Women and Girls Take Action" is a 2-year project based at the Antigonish Women's Resource Centre & Sexual Assault Services Association. The goal of the project is to engage young people and communities in raising awareness about, and taking steps to end, violence against young women and girls. I began working as the project coordinator on January 31st. The project is funded by Status of Women Canada.

Here's the url for the Resisting Violence Page. I encourage you to check it out!

http://antigonishwomenscentre.com/resistingviolence/index.html

Here's the url for the Resisting Violence Page. I encourage you to check it out!

http://antigonishwomenscentre.com/resistingviolence/index.html

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

2nd Pan-Canadian Young Feminist Gathering - Promotional video!!!

Some of you may have heard about the upcoming Pan-Canadian Young Feminist Gathering that will take place from May 20-23rd in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It's the 2nd gathering of its kind; the first happened in 2008 in Montreal. Check out the promotional video!

If you're living in Nova Scotia and are interested in attending the gathering, drop me a line at betsypd@gmail.com . You can also check out http://www.rebelles.org/ for more info!

Betsy

If you're living in Nova Scotia and are interested in attending the gathering, drop me a line at betsypd@gmail.com . You can also check out http://www.rebelles.org/ for more info!

Betsy

Monday, March 28, 2011

Cyberbullying linked to suicide

I recently heard the news about a Nova Scotia teen, Jenna Bowers-Bryanton, who took her own life in January. It turns out that she was a victim of online bullying, and her death has motivated loved ones to launch a campaign to end cyberbullying. Here's an article about the campaign:

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/story/2011/03/28/ns-jenna-cyberbullying.html

Jenna's story has caused me to reflect on what the internet, and social networking in particular, means to young people. As a somewhat young person myself, I (admittedly) spend quite a bit of time on Facebook. Given that Facebook only emerged a few years ago, though, it was never part of my experience as a high school student. In many ways I'm glad, because I was already a pretty insecure teen and social networking probably would have just exacerbated my insecurities. Then again, who knows? At any rate, it's kind of a moot point because social networking is an important aspect of many people's lives. How can we make cyberspace a safe space, and not a dangerous one, for those of us who spend time online?

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/story/2011/03/28/ns-jenna-cyberbullying.html

Jenna's story has caused me to reflect on what the internet, and social networking in particular, means to young people. As a somewhat young person myself, I (admittedly) spend quite a bit of time on Facebook. Given that Facebook only emerged a few years ago, though, it was never part of my experience as a high school student. In many ways I'm glad, because I was already a pretty insecure teen and social networking probably would have just exacerbated my insecurities. Then again, who knows? At any rate, it's kind of a moot point because social networking is an important aspect of many people's lives. How can we make cyberspace a safe space, and not a dangerous one, for those of us who spend time online?

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

Purple Ribbon Campaign in Newfoundland & Labrador

The government of Newfoundland & Labrador is carrying out a violence prevention initiative that includes a Purple Ribbon Campaign focused on educating the public about, and working to end, violence against women. Here is the website for the campaign:

http://www.respectwomen.ca/

It's got some great resources for survivors of male violence against women, as well as perpetrators, friends, and parents who wish to teach non-violence to their children. There are also lots of good facts on violence against women available on the site.

This is a great resource and something that would be very useful in Nova Scotia...

http://www.respectwomen.ca/

It's got some great resources for survivors of male violence against women, as well as perpetrators, friends, and parents who wish to teach non-violence to their children. There are also lots of good facts on violence against women available on the site.

This is a great resource and something that would be very useful in Nova Scotia...

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

Happy (belated) International Women's Day!

Well, I had such a busy (and wonderful!) International Women's Day that I didn't get a chance to post anything until now. Just wanted to say happy IWD to all of you, and let us take this week as an opportunity to reflect on the hard work and incredible achievements of our feminist foremothers, and also consider the hard work that lies ahead. Violence against women and girls is still pervasive in Canada and all over the world. Women still earn less than men but perform the majority of the world's work. Women and girls are hypersexualized, degraded and objectified through our media and expected to conform to an increasingly pornographized standard of beauty. Women experience oppression on the basis of sex, gender, class, race, ethnicity, indigeneity, ability, sexual orientation, age, language, geography, political affiliation, citizenship status and religion. Through our taxes, we are made to pay for a war machine created by a handful of extremely privileged men in order to profit from the destruction of life. Regressive policies in our country make the prospect of affordable childcare and affordable housing seem like a distant dream, unless there is serious political change.

The 100th anniversary of International Women's Day marks an important time for women in history. It is a time to celebrate our strenghts and diversity, and to move forward with great courage, clarity and (com-)passion. To quote the Hopi elders, "We are the ones we have been waiting for."

Betsy

The 100th anniversary of International Women's Day marks an important time for women in history. It is a time to celebrate our strenghts and diversity, and to move forward with great courage, clarity and (com-)passion. To quote the Hopi elders, "We are the ones we have been waiting for."

Betsy

Monday, February 21, 2011

More Sisters in Spirit links

For those of you who are interested in learning more about Sisters and Spirit and would like to support this vital initiative, here are some good links:

Petition: Support the Native Women's Association of Canada http://www.nwac.ca/sisters-spirit-supporters

Sisters in Spirit website http://www.nwac.ca/programs/sisters-spirit

Ways to Support Sisters in Spirit http://www.psacbc.com/2010/08/12/5788/

KAIROS: Take Action to Support Sisters in Spirit http://www.kairoscanada.org/en/dignity-rights/indigenous-rights/sisters-in-spirit/takeaction/

Petition: Support the Native Women's Association of Canada http://www.nwac.ca/sisters-spirit-supporters

Sisters in Spirit website http://www.nwac.ca/programs/sisters-spirit

Ways to Support Sisters in Spirit http://www.psacbc.com/2010/08/12/5788/

KAIROS: Take Action to Support Sisters in Spirit http://www.kairoscanada.org/en/dignity-rights/indigenous-rights/sisters-in-spirit/takeaction/

New name and web address!

Hey everyone! If you're reading this, you've probably noticed that the blog has a new name - Women and Girls Take Action! I thought it would be good to shift the focus a bit, since the focus of my own work has shifted from securing funding for women's services to working with youth to develop community-based action strategies for resisting violence against women and girls. Feel free to use the blog as a space to share your stories and your ideas for taking action! Also, please share the new web address (http://womenandgirlstakeaction.blogspot.com/) with your friends, family, co-workers and anyone else who might be interested! Thanks,

Betsy

Betsy

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)